When people imagine engineering work, they picture clean CAD models, glossy renderings, and polished prototypes that look ready for a brochure. The reality is very different.

A surprising amount of progress happens while holding something that looks like it came out of a recycling bin. Terrible prototypes are not a byproduct of design. They are the first design tool that tells the truth.

This idea ties directly into our philosophy at Kotatsu. A kotatsu is a Japanese heated table that warms only the place where the person is. It focuses energy precisely where it provides the most comfort. Terrible prototypes work the same way. They focus the design team's attention exactly where understanding is coldest and where assumptions need heat.

Let’s look at why they are so valuable.

1. Terrible prototypes expose what FEA hides

FEA is powerful, but it is also polite. It tells you exactly what your assumptions produce by analyzing the input Boundary Conditions. What it does not tell you is whether those Boundary Conditions were reasonable.

In most early models, we simplify the world into perfect constraints, ideal contacts, and tidy load paths. The real world rarely cooperates.

A terrible prototype captures the truth immediately:

- Real constraint stiffness, not the perfectly rigid fixture you used in the model

- Real friction in joints

- Real misalignment between features

- Real manufacturing variation

- Real load paths that no amount of meshing intuition can reveal

If your prototype breaks in a place you never analyzed, it just taught you something FEA would have never volunteered on its own.

2. They force ergonomic honesty

CAD lies about ergonomics. Every designer has experienced this.

In the model, everything looks reachable and comfortable. In your hands, it becomes clear that your beautiful lever is at the wrong angle, the grip is too large, and your wrist needs to be double jointed to operate it.

A terrible prototype tells you the truth in the first five seconds. It reveals:

- Where fingers pinch

- Where your wrist twists awkwardly

- How much force a task truly requires

- How intuitive the control layout feels

- Real Haptic Feedback, such as how the material feels, how much effort is required to move a mechanism, and the vibrational response

Digital ergonomics is helpful, but nothing replaces holding a flawed physical sample and letting your hands react before your brain can rationalize.

3. They expose assembly realities immediately

Every engineer has had this experience.

The CAD assembly builds perfectly.

The actual assembly is a comedy.

Terrible prototypes show you the real constraints instantly:

- The bolt is reachable in CAD but unreachable with any real tool

- You need three hands to hold the parts together

- The alignment feature is decorative at best

- The part only fits if you break several laws of geometry

- The fasteners interfere with components that CAD forgot to tell you about

You learn what your model assumed and what your drawing never communicated, saving hours of redesign and expensive manufacturing rework.

4. They show you where precision actually matters

A rough prototype has sloppy tolerances everywhere. That is the point.

Where it fails first tells you where precision truly belongs.

Suddenly you know:

- Which faces actually need flatness

- Which holes need positional accuracy

- Which interfaces must be located, and which can float

- Which clearances matter for function

- Which tolerances will spike cost downstream

This insight is impossible to gain without seeing what breaks when everything is inaccurate by default. It is the most efficient method for determining your final Geometric Dimensioning and Tolerancing (GD&T) strategy.

5. They teach the team more than a perfect prototype ever will

Perfect prototypes tell you what you already got right. Terrible prototypes tell you what you never even considered.

More importantly, they create shared understanding. When a team crowds around a bad prototype, nobody is arguing about theory. They are pointing at physical reality.

- This sticks

- That wiggles

- This feels wrong

- That binds

- This is too stiff

- That is too flexible

Now everyone has the same picture.

A useful comparison from software: MVP thinking

The software world has a concept called the Minimum Viable Product. An MVP is not the final product. It is not even a good product. It is the smallest, roughest version that still teaches you something important about the user, the process, or the system.

Terrible prototypes play the same role in physical engineering.

Just like MVPs, they exist to:

- Test assumptions early

- Challenge the team's intuition

- Reveal hidden requirements

- Uncover usability problems

- Provide fast feedback from real interaction

- Prevent investment in the wrong idea

A physical prototype held together with tape has the same purpose as a minimal software build held together with temporary logic. Neither is meant to be pretty. Both are meant to surface the truth long before the cost of being wrong becomes painful.

Software teams iterate quickly because they learn quickly. Engineering teams that build terrible prototypes do the same.

Physical MVPs are simply terrible prototypes with a more respectable name.

A concrete example

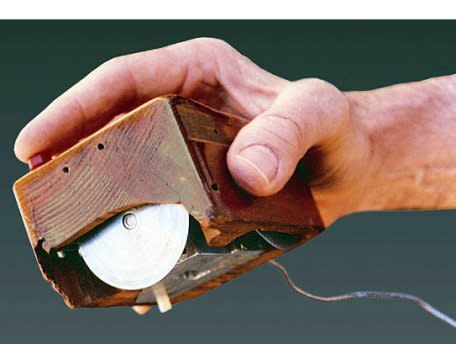

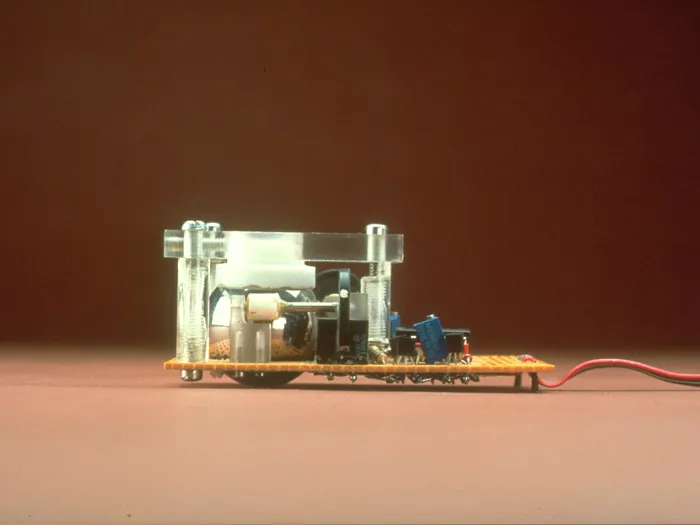

Consider how many world changing products began as terrible prototypes.

Some of the most iconic products were shaped by terrible prototypes. The pattern is always the same: build something rough, learn fast, then refine.

Consider a more ordinary example. Take the first 3D printed handle for a power tool. In CAD, the grip looks fine. On the one dollar prototype, you immediately feel that the diameter is wrong, your palm sits in the wrong place, and the torsional load makes the tool want to rotate out of your hand. You learn in seconds that you need a different texture, a different offset, and a different mass distribution. That is a lesson that would take hours of analysis and digital ergonomics work to approximate, and even then it would not be as clear.

The Kotatsu connection

A terrible prototype warms the engineering effort exactly where understanding is cold. It reveals the places where your assumptions are thin and where your intuition needs recalibration. It shines heat on the cold spots in your design long before you have invested serious time or money.

In the end

Beautiful prototypes impress people. Terrible prototypes teach people.

If you want a product that works in the real world, start with something that forces you to confront reality. Start with a terrible prototype. It is the fastest way to get to a beautiful solution.

Related reading: GD&T - The Designer’s Steering Wheel

Kotatsu Design & Development Inc.

Kotatsu Design & Development Inc.