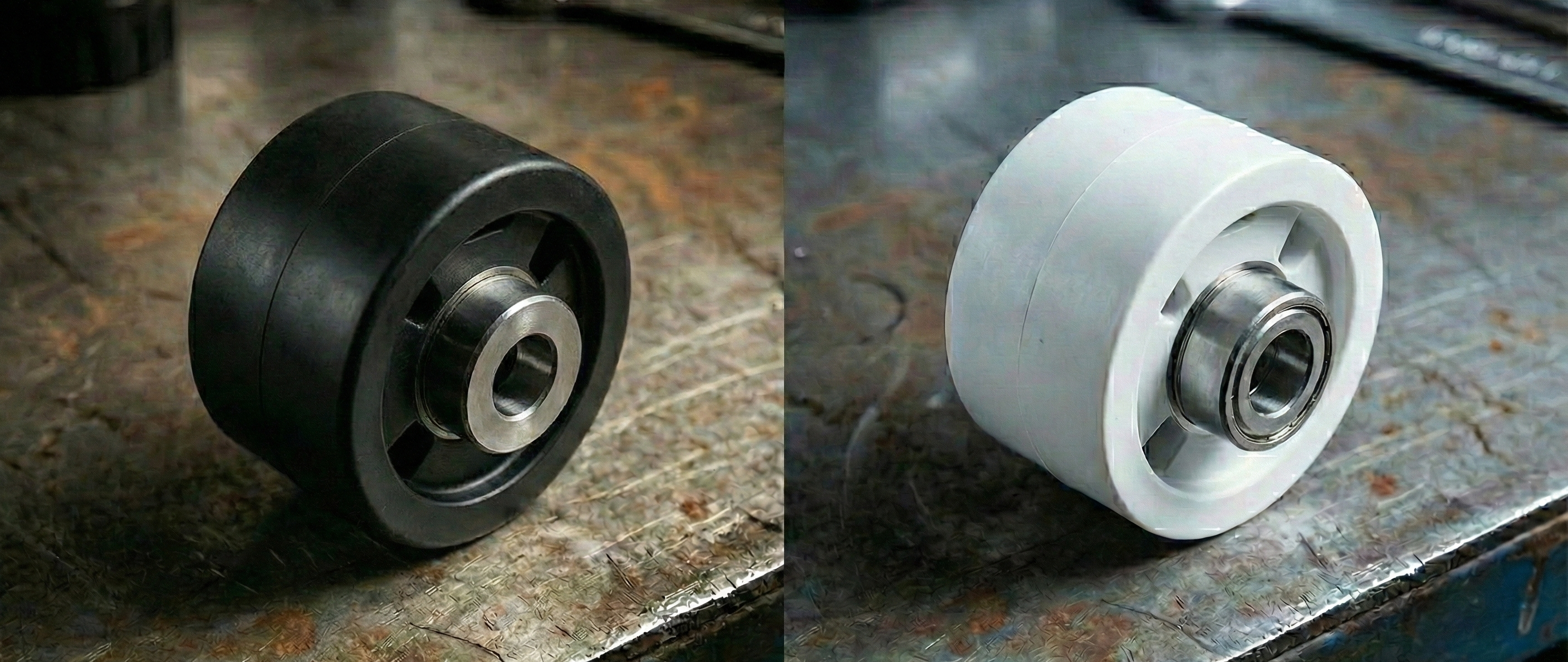

At some point, every engineer notices it:

“Why is this rubber black… and this one white?”

“Is it just colour?”

“Can’t we just swap materials?”

Short answer: No.

Long answer: the colour is telling you something important about how that rubber will behave under load, over time, and in the real world.

Let’s talk about carbon black vs. mineral fillers, and why that choice quietly controls stiffness, durability, fatigue life, damping, and cost.

1) Rubber is not rubber — it’s a composite

Unfilled rubber is almost useless for real products. What we call “rubber” is actually:

- A polymer matrix (EPDM, NR, NBR, SBR, etc.)

- Plus fillers

- Plus curatives, oils, stabilizers, and processing aids

The filler does the heavy lifting — mechanically, thermally, and dynamically.

In most applications, fillers account for 30–50% of the compound by weight and a large portion of the mechanical properties. The two most common filler families are:

- Carbon Black → The structural standard (black rubber)

- Mineral Fillers → The specialists (white or coloured rubber)

They are not interchangeable.

2) Carbon black: The structural workhorse

Carbon black isn’t there for colour; the black pigment is just a side effect. What carbon black actually does:

- Reinforces rubber at the molecular level

- Increases tensile strength and tear resistance

- Dramatically improves fatigue life

- Enhances abrasion resistance

- Improves thermal conductivity (important for heat dissipation)

Carbon black particles form strong physical and chemical interactions with the polymer chains. That interaction is why black rubber survives suspension bushings, engine mounts, tires, and dynamic seals.

3) The world of white fillers: Clay, chalk, and silica

Not all white fillers are created equal. We generally split them into two camps.

The cost-savers: Clay and calcium carbonate

These are often used as extenders — they take up space to reduce the amount of expensive polymer required.

They:

- Increase stiffness cheaply

- Improve dimensional stability

But they also:

- Offer poor tensile strength and tear resistance

- Have much worse fatigue life than carbon black

They do not reinforce rubber in a structural sense.

The exception: Silica

Precipitated silica is a high-performance white filler used in modern tires and aerospace elastomers.

Silica can be structural, but it:

- Is difficult to process

- Requires specialized coupling agents

- Is expensive

- Is highly compound-specific

Rule of thumb: Unless your part was explicitly engineered with high-grade silica (think high-end sneaker soles or racing tires), a white rubber part is almost certainly clay-filled — and it will not behave like carbon black.

4) Why engineers still use white rubber

White-filled rubbers exist for legitimate reasons:

- Electrical insulation: Carbon black is inherently semi-conductive (depending on grade and loading). It occupies a difficult middle ground — conductive enough to fail as a true insulator, but often too resistive to act as a reliable system ground. (This is why conductive straps are often used to bridge black rubber engine mounts.) If you need true electrical isolation, mineral fillers are required.

- Colour coding: If the part must be medical-grade, food-grade, or safety-orange, carbon black is not an option.

- Non-marking requirements: For caster wheels, shoe soles, or clean-room bumpers, carbon black is often banned because it leaves streaks.

- Static applications: If the part barely moves and isn’t fatigue-critical, white fillers are often sufficient — and cheaper.

5) Fatigue is where the difference really shows

Under cyclic load, the difference is brutal.

Carbon black particles form strong interactions with rubber chains, distributing stress smoothly throughout the compound. Clay particles often just “sit” in the rubber matrix.

Under repeated stretching:

- The rubber pulls away from the clay particle

- Microscopic voids form

- Voids grow and link

- A crack initiates

The cycle comparison

- Carbon Black: Flexes → relaxes → repeats

- Clay / Mineral: Voids form → voids join → part fails

Hardness is a surface measurement; fatigue life lives inside the compound.

6) Damping, NVH, and “feel”

Carbon black also affects dynamic behavior, offering more predictable hysteresis and more consistent vibration control across temperature.

White-filled rubbers can often feel plasticky or damp inconsistently.

If the rubber part exists to control noise, vibration, or tactile feel, black rubber usually offers more stable performance.

7) Cost: The quiet driver

General-purpose clay and calcium carbonate are significantly cheaper than carbon black. Silica, by contrast, is usually more expensive.

So you’ll often see:

- White or grey rubber where cost is the dominant driver

- Black rubber where performance matters

A failed rubber part costs warranty claims, downtime, and redesign effort. The pennies saved per part on clay fillers are never worth it.

Closing thought

Rubber colour is a clue, not a preference.

- Black rubber usually signals reinforcement, fatigue resistance, and durability.

- White rubber usually signals cost control, electrical insulation, or cosmetic and non-marking requirements.

If a rubber part is failing and the datasheet isn’t telling you why, the filler choice is often the missing piece.

Don’t guess — check the compound.

Kotatsu Design & Development Inc.

Kotatsu Design & Development Inc.